More often than not, a player who specializes in one aspect of the game is known just for that. There are some exceptions, however. Hall of Famer Bill Mazeroski was a defensive wizard at second base for the Pittsburgh Pirates from the mid-1950s to the early 1970s. During his 17-year career, Mazeroski won eight Gold Glove awards, a number that has been surpassed by just two second basemen, both of whom are in the Hall of Fame (Ryne Sandberg, Roberto Alomar). But unlike Sandberg and Alomar, who were as lethal with the bat as they were with the glove, Mazeroski was not a particularly good hitter.

Mazeroski's lifetime .260 batting average and .299 on-base percentage weren't exactly Hall of Fame-caliber numbers. Neither were his 138 homers, 853 RBI or 769 runs scored. But one post-season home run catapulted Maz to legendary status and became one of the contributing factors in his selection to the Hall of Fame by the Veteran's Committee nearly 30 years after he played his final game.

That World Series-winning blast against the heavily-favored Yankees in 1960 became Maz's calling card, almost completely overshadowing what he did on the field with his glove. Mazeroski is one of a few players who specialized in one thing on the baseball field, but whose signature moment came in a spot that was ordinarily his weakness.

Likewise, the Mets had such a player in the early days of the franchise - a player who was one of the team's best power-hitting prospects when he was first called up in 1965, then became a player of legend four years later. But of course, it wasn't his bat that made him a storied Met. Rather, it was one spectacular defensive play at a most critical juncture that elevated him to heroic levels.

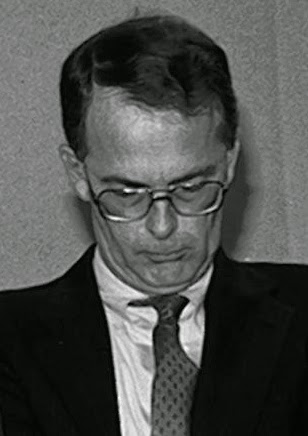

|

| A young Ron Swoboda was an all-hit, no-glove player. But Mets fans loved him for his glove in 1969. |

Ronald Alan Swoboda was known as a power hitter from a very young age. As a 19-year-old, his penchant for hitting balls a long way caught the eye of the Mets, who signed him in 1963 after he completed his freshman year at the University of Maryland. Swoboda played one season in the Mets minor league system before making the team's Opening Day roster in 1965.

Swoboda became an instant success in New York, collecting 10 home runs in his first 90 at-bats. In addition, half of Swoboda's first 28 hits went for extra bases. Although Swoboda collected only 399 at-bats in 1965, he still managed to lead the team in home runs (19) and slugging percentage (.424), while finishing third on the club in RBI (50) and second in runs scored (52).

Casey Stengel was an ardent supporter of Swoboda, and he showed his loyalty to the 20-year-old outfielder by starting him in 67 of the team's first 96 games. But once Casey was forced to step down as Mets manager because of a hip injury in late July, Swoboda's performance on the field suffered and his playing time decreased. Swoboda started just 37 of the Mets' final 67 games in 1965, batting .191 with three homers and 11 RBI over the final two and a half months of the season.

Swoboda did not play as much in 1966, collecting only 342 at-bats, but he drove in 50 runs for the second straight season despite batting just .222 with 21 extra-base hits. The reason why Swoboda drove in so many runs in limited playing time was because he was an excellent clutch hitter. With no one on base, Swoboda batted .197 in 1966. But with runners in scoring position, his average ballooned to .326. Swoboda also posted a .605 slugging percentage and a whopping 1.037 OPS in RBI situations in 1966. He followed that up with a similar season in 1967, batting .320 with runners in scoring position.

Although Swoboda was never much of a high average hitter (he batted above .242 just once in his six seasons with the Mets), he always hit well and hit with power when there were runners on base. More than half (36) of his 69 career homers as a Met came with runners on base. He also batted .275 with two outs and runners in scoring position.

From 1965 to 1969, Swoboda never amassed more than 450 at-bats in any season. However, he did manage to drive in 50 or more runs in each of his first five seasons with the Mets. In doing so, he became just the 26th player (and first Met) in modern National League history to accomplish this feat, joining all-time greats such as Johnny Mize, Ralph Kiner, Eddie Mathews, Hank Aaron, Orlando Cepeda and Frank Robinson.

After the retirement of Casey Stengel, Swoboda never fully took over as the everyday player Stengel projected him to be, especially after Gil Hodges became the team's manager in 1968. In 1969, Swoboda - a right-handed hitter - shared duties in right field with the lefty-swinging Art Shamsky and switch-hitter Rod Gaspar. As good as Swoboda was hitting in the clutch and hitting with power, he was just as bad with a glove on his hand. Never known for his fielding prowess (although he did possess a fine arm in the outfield), Swoboda occasionally lost playing time to the slick fielding Gaspar, even when a left-handed pitcher was on the mound. Because of his fielding ineptitude and Hodges' strict adherence to the outfield platoon, Swoboda collected just 327 at-bats in 1969 - his lowest total in his first five years. But Swoboda made the most of his limited opportunities.

During the Mets' miraculous late-season run in 1969, Swoboda hit his first career grand slam, an eighth-inning shot against the Pirates that a broke a 1-1 tie and sent the Mets to their tenth consecutive victory. Two days later, Swoboda hit another go-ahead homer in the eighth inning. It was Swoboda's second two-run homer of the contest against Cardinals starting pitcher (and future Hall of Famer) Steve Carlton. Swoboda was only in the starting lineup because Carlton was a southpaw. But without Swoboda's heroics, the game would have been remembered more for Carlton's epic 19-strikeout performance - the first time in major league history that a pitcher had as many as 19 whiffs in a nine-inning game.

With all the success he had as a hitter during his first five seasons in the majors (especially during the September run to the NL East crown in 1969), one would think that Swoboda would forever be part of Mets lore because of what he accomplished with the bat. Perhaps that would have been true had it not been for what transpired in the ninth inning of Game Four in the 1969 World Series.

Ron Swoboda had the third-highest RBI total on the 1969 Mets despite having the eighth-most at-bats on the team. But even though Swoboda had displayed a keen ability to drive in runs, manager Gil Hodges stayed true to his style and kept him on the bench during the Mets' three-game sweep of the Atlanta Braves in the inaugural National League Championship Series. Atlanta's three starting pitchers in the series - Phil Niekro, Ron Reed and Pat Jarvis - were all right-handed, thereby allowing Hodges to start Shamsky in right field for all three games, with Gaspar coming in as a defensive replacement in the late innings. But the World Series was a different story, as the American League champion Baltimore Orioles had two left-handed starters in Mike Cuellar and Dave McNally. Swoboda would finally get his first taste of the postseason in Game One of the 1969 World Series.

After striking out and flying out in his first two World Series at-bats, Swoboda caught fire. He reached base seven times in his next 14 plate appearances, collecting five singles, a double and a walk. But it was what he did between his 11th and 12th World Series plate appearances that may have helped save the season for the Mets.

The Mets had won two of the first three games against Baltimore and were looking to take a commanding 3-to-1 series lead in Game Four at Shea Stadium. Any loss by the Mets at home would guarantee that the series would go back to Memorial Stadium, where the Orioles posted a league-best 60-21 record in 1969. Needless to say, the Mets did not want to go back to Baltimore.

Game Four was a pitchers' duel between Tom Seaver and Mike Cuellar. Cuellar pitched seven innings of one-run ball, while Seaver held the Orioles scoreless through eight innings. Clinging to a precarious 1-0 lead in the ninth inning, Seaver was sent back to the mound to finish what he started. But after retiring Paul Blair on a fly ball to Swoboda, Seaver allowed back-to-back hits to Frank Robinson and Boog Powell, with the latter hit moving Robinson to third base. That brought up third baseman Brooks Robinson, who lined a ball that appeared headed for the gap in right-center. But Swoboda ran at full speed and made a diving lunge at the ball, catching it a millisecond before it hit the outfield grass.

"If that shot had been hit straight at me, it might still be rolling. For me, it was one of those do-or-die plays. There's one chance in a thousand I'm going to catch it, but I had to go for it. Chalk it up to a blind squirrel finding an acorn."

Although Frank Robinson scored the tying run from third base on the sacrifice fly by Brooks Robinson, it was Swoboda's athletic grab that prevented the ball from rolling all the way to the wall, keeping the Orioles from taking the lead. As a result, Baltimore failed to score the go-ahead run in the ninth inning, allowing the Mets to push across the winning run in the bottom of the tenth inning on a throwing error by relief pitcher Pete Richert.

The catch by Swoboda did not win the series, let alone the game, for the Mets, but it thwarted Baltimore's best chance to come back in a series that by all intents and purposes, was theirs to lose. The Orioles had come into the series with 109 regular season victories - a number that had been surpassed by just four teams before them. But after Swoboda's catch and the subsequent win by the Mets an inning later, the wind was knocked out of Baltimore's sails.

Brooks Robinson clearly felt as if Swoboda's catch was the turning point of the series. "If the ball gets by Ron," said the Orioles' 16-time Gold Glove winner, "two runs score, we win 2-1, and the Series is tied 2-2. I'll always feel that way. That play was a killer."

One day after his unbelievable and unexpected catch, Swoboda once again came through for the Mets in the late innings, although this time it was with his more familiar weapon of choice - his bat.

The Mets had rallied from an early three-run deficit, tying it on a two-run homer by slugger Donn Clendenon in the sixth inning and a solo shot by non-slugger Al Weis in the seventh. With the game now tied, 3-3, the Mets were poised to take the lead in the eighth inning. Cleon Jones led off the frame with a double off reliever Eddie Watt. Jones remained at second after Watt coaxed Clendenon to ground out to third. Up stepped Ron Swoboda, clutch hitter extraordinaire, with a chance to be the hero for the Mets. And as he did so many times before, Swoboda came through.

Video courtesy of the MLB.com YouTube channel

Swoboda ripped a double near the left field line, a hit that fell just in front of a non-diving Don Buford, who chose not to take a page out of the Ron Swoboda Handbook for Game-Saving Plays. The two-bagger scored Jones from second to give the Mets a lead they would not relinquish, as Swoboda scored an insurance run on Boog Powell's error later in the inning and Jerry Koosman got the final three outs in the ninth to secure the Mets' first World Series championship.

Although Donn Clendenon was voted the 1969 World Series Most Valuable Player, the award could have easily gone to Swoboda, as the Mets' right fielder produced a .400 batting average with a team-leading six hits, despite not playing in Game Three because right-handed starting pitcher Jim Palmer was on the mound for Baltimore. Swoboda also made the game-saving catch in Game Four and delivered the game-winning hit in the Mets' World Series-clinching victory.

Ron Swoboda was a tremendous run-producer with the Mets in a limited number of plate appearances. And on a team that has seen so many All-Star sluggers and run producers, Swoboda matches up favorably when it comes to producing runs. Here are some things you may not have known about Swoboda as a hitter:

- Ron Swoboda's total of 19 home runs as a rookie in 1965 has been surpassed by just one Mets first-year player - Darryl Strawberry. The Straw Man's 26 homers in 1983 broke Swoboda's rookie mark nearly two decades after the mark was set. Only Ike Davis in 2010 has been able to match Swoboda's mark in the years since Strawberry broke the team record for homers by a rookie.

- When Swoboda played his final game as a Met in 1970, he was the team's all-time leader in home runs (69) and RBI (304). He wasn't knocked out of the top ten in homers until 1988, when Keith Hernandez passed him on May 18. Swoboda was in the team's top ten in RBI until 1986, when Lee Mazzilli displaced him on August 13.

- Through the 2014 season, Swoboda remains just one of 11 players in Mets history to have at least five seasons with 50 or more RBI. The other ten are a who's who of great Mets hitters - Keith Hernandez, Howard Johnson, Kevin McReynolds, Edgardo Alfonzo, Carlos Beltran, Jose Reyes, Cleon Jones, Darryl Strawberry, Mike Piazza and David Wright.

- Swoboda produced five 50-plus RBI seasons with the Mets despite never having more than 450 at-bats in any season. He remains the only Met to have that many 50-RBI campaigns in seasons he didn't surpass 450 at-bats. Stretching it out by 50 at-bats, Swoboda joins all-time great Mike Piazza as the only Mets to achieve five 50-RBI seasons in years with 500 or fewer at-bats.

Ron Swoboda didn't possess a high batting average, nor did he wear a glove made of gold in the field. But he did have many memorable moments, primarily as a hitter and especially during the months of September and October in 1969. Yet despite those impressive credentials as a hitter, Swoboda will always be remembered for one thing before anything else.

In 1969, the Mets needed to win Game Four of the World Series to potentially avoid a return trip to a hostile environment in Baltimore. The Orioles won 60 games at home in 1969, which was a higher win total than the Mets produced in all games, at home AND on the road, in each of their first four seasons. Ron Swoboda, a Baltimore native, had done whatever he could with the bat to help his team. But in Game Four, he stretched his baseball ability - and his body - to a place no one expected. With one Amazin' catch, Swoboda propelled the Mets to victory in Game Four, and helped seal the team's improbable championship the following day.

Ron Swoboda was supposed to be a great catch by the Mets when they signed him to a contract in 1963. Six years later, he gave the team his own version of a great catch. Swoboda may have originally been coveted for his bat, but it's his glove that will always provide fond memories for Mets fans young and old. His defining moment occurred during one of the greatest times to be a Mets fan and will always be among the brightest spots in the history of the franchise.

|

| Miracles do happen. Just ask Ron Swoboda. |

Note: One Mo-MET In Time is a thirteen-part weekly series spotlighting those Mets players who will forever be known for a single moment, game or event, regardless of whatever else they accomplished during their tenure with the Mets. For previous installments, please click on the players' names below:

January 5, 2015: Mookie Wilson

January 12, 2015: Dave Mlicki

January 19, 2015: Steve Henderson