The Mets have had both types of "next big thing" players. They've had the success stories who played incredibly well in a Mets uniform, like Tom Seaver and Darryl Strawberry. But they've also had guys who didn't quite live up to the lofty expectations. Players like Gregg Jefferies and Paul Wilson come to mind.

It's bad enough when one of these supposed sure things flames out at the big league level. But it's far worse when that player is so highly touted that he ends up replacing an established veteran - only to have the veteran continue to play at a high level long after the so-called phenom's star has fizzled.

In 1975, the Mets fell into that trap, letting a one-month hot streak by a neophyte dictate whether or not they needed to keep an aging star. They made the wrong decision, and in doing so, changed the fortune of the team for the better part of a decade.

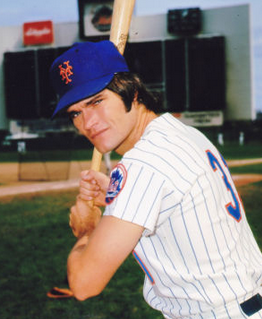

|

| Mike Vail's one good month caused the Mets to have seven bad years. |

Michael Lewis Vail was drafted by the St. Louis Cardinals in 1971 as an infielder who occasionally played in the outfield. Vail struggled as a hitter in his first two minor league seasons, batting .235 in just under 500 at-bats, causing him to be demoted from the Double-A level back to Single-A for the start of the 1973 season. But Vail started to turn things around in 1973, raising his average to .278, while banging out 31 doubles, nine triples and 15 homers. In 1974, Vail's power production remained consistent, but his batting average soared to .334. That caught the eye of the Mets' front office, who traded utility player Ted Martinez to the Cardinals for Vail and infielder Jack Heidemann in December.

Leaving the Cardinals organization did nothing to impede Vail's development, as he proceeded to bat .342 at Tidewater in 1975, posting an outstanding .888 OPS with the Mets' Triple-A affiliate. For his efforts, Vail was named the International League Player of the Year and earned his first promotion to the big leagues.

Prior to Vail's promotion in August, the Mets had used six different left fielders, with none of them having started more than 64 games at the position. Vail made his major league debut on August 18, collecting a pinch-hit single off Houston's hard-throwing right-hander J.R. Richard. Vail became the seventh Met to start a game in left field two days later, but went 0-for-5. Through his first four games at the big league level, Vail collected three hits in 11 at-bats. He more than doubled his career hit total in his fifth game - a game that began Vail's march into the record books.

Facing the San Diego Padres on August 25, Vail went 4-for-4 with a walk, becoming the first Met to collect four hits in a game during his first month in the big leagues. Vail collected three hits the following day and two more hits in the series finale against the Padres. But as August turned to September, the Mets faded from the NL East race. A victory over the Pirates on September 1 - a game in which Vail hit his first major league home run - moved the Mets to within four games of first place Pittsburgh. The joy was short-lived, however, as the Mets proceeded to lose eight of their next nine games to fall ten games out of first.

The Mets may have stopped winning in September, but Vail never stopped hitting. By September 9, Vail was hitting .358 and had recorded eight multi-hit games in his first 18 starts. Three days later, Vail extended his hitting streak to 20 games, making him just the third Met to collect a hit in 20 or more consecutive games, joining Tommie Agee and Cleon Jones, who both accomplished the feat in 1970. The hit streak by Jones eventually reached 23 games, and on September 15, Vail matched him.

Trailing 2-0 in the sixth inning against the Montreal Expos, Vail delivered a two-out, run-scoring single off Steve Rogers. Vail not only cut the Expos' lead in half, but he extended his hitting streak to 23 games, tying Cleon Jones's franchise record and the modern National League record for rookies. Vail joined Joe Rapp (1921), Alvin Dark (1948) and Richie Ashburn (1948) as the only Senior Circuit rookies to string together a hitting skein of 23 games. Two innings later, Vail delivered his second hit of the game, an RBI single that scored the decisive run in the Mets' 3-2 victory.

Unfortunately, Vail could not break the Mets' record for longest hitting streak, even though he got plenty of opportunities to do so. On September 16, during an 18-inning marathon against the Expos, Vail drew a first-inning walk, then failed to collect a hit in his next seven plate appearances. When Del Unser drew a bases-loaded walk to force in the winning run in the Mets' 4-3 victory, Vail was two batters away from getting a ninth chance to extend his streak.

With the streak now in the past, the Mets could contemplate their future - one that involved Mike Vail as an everyday player. But Vail's future in New York was not in left field. Rather, it was in right, a position that was occupied by Rusty Staub, who had just completed the first 100-RBI campaign in Mets history.

Staub had already played 13 seasons in the major leagues and was thought to be entering the downside of his career. Plus, with slugger Dave Kingman setting a franchise record by hitting 36 home runs in 1975, Staub was deemed expendable. The Mets were also searching for a fourth starter to use behind Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman and Jon Matlack, and believed they had found him in Detroit in 207-game winner Mickey Lolich. General manager Joe McDonald was certain that Vail was ready to replace Staub in right, and thought of something the Brooklyn Dodgers had done in the early 1940s.

"When we won in 1973, George Stone won 13 games. But the last two years, we haven't had a consistent fourth starter. Stone had arm trouble and Randy Tate and Craig Swan couldn't quite do it. In getting Lolich, it reminds me of when the old Brooklyn Dodgers were winning with Larry French as their fourth starter."

If that was the reason McDonald acquired Lolich, then the Mets were in serious trouble. For one thing, French only started 15 games for the Dodgers in 1941 and 1942, appearing in relief 29 times. In his only full season with the Dodgers (1942), French did pitch beautifully, going 15-4 with a 1.83 ERA. But the Dodgers didn't win the pennant in 1942, finishing two games behind the eventual World Series champion Cardinals. They did advance to the World Series the previous year, but French only started one game for the Dodgers in 1941. (And not to nitpick, but McDonald's selective memory also pegged George Stone as a 13-game winner in 1973 when he only won a dozen games.)

While it was true that Mickey Lolich had had a solid career in the majors, winning 207 games prior to being traded to the Mets for Rusty Staub, McDonald failed to notice one important detail about Lolich's career. In his first eight years in the big leagues (1963-70), Lolich never pitched more than 280⅔ innings in any season. But from 1971 to 1974, Lolich never pitched fewer than 308 innings, peaking in 1971 when he tossed a mind-boggling 376 innings in 45 starts.

Staub had come off a 1975 season in which he received MVP consideration. Lolich was coming off a 1975 campaign in which he went 12-18 and pitched just 240⅔ innings, his lowest total since 1968. Lolich might have been able to give the Mets the innings they needed out of a fourth starter, but he certainly wasn't going to help them win. In other words, Lolich was not going to be the Mets' version of Larry French, something that was confirmed when Lolich went 8-13 and pitched just 192⅔ innings in his only season as a Met.

While Joe McDonald was busy trading away his MVP candidate for a washed-up pitcher, Mike Vail was busy getting hurt playing basketball. A dislocated right foot suffered in January caused Vail to miss half of the 1976 season. Upon his return, Vail spent most of June and July on the bench, starting just six games over the two months. Vail played in just 53 games in 1976, batting .217 in 143 at-bats. His total of 31 hits during the 1976 campaign was three fewer than the number of hits he collected during his 23-game hitting streak the previous summer.

Vail played one more season with the Mets in 1977, but never hit enough to play every day. He shared right field duties with Dave Kingman and Ed Kranepool during the season's first half, then ended the year in a right field platoon with Bruce Boisclair. Vail was then claimed off waivers by the Cleveland Indians prior to the start of the 1978 season.

In three years with the Mets, Vail produced a total of 25 doubles, 11 homers and 61 RBI. In his first three years with Detroit following the trade to make room for Vail, Rusty Staub averaged 31 doubles, 20 homers and 106 RBI per season. Needless to say, Vail didn't exactly make Mets fans forget about Rusty Staub.

In three years with the Mets, Vail produced a total of 25 doubles, 11 homers and 61 RBI. In his first three years with Detroit following the trade to make room for Vail, Rusty Staub averaged 31 doubles, 20 homers and 106 RBI per season. Needless to say, Vail didn't exactly make Mets fans forget about Rusty Staub.Throughout the team's history, many young players have been viewed as the next great Mets prospect. For Mike Vail, an unexpected long hitting streak that began a week after he made his major league debut gave the team hope that it had found its newest young star - one that could shine at Shea Stadium for many years to come.

Unfortunately for Vail, his rookie record lasted longer than his time in the major leagues. And unfortunately for the Mets, Rusty Staub still had several All-Star caliber seasons left in him after they traded him away.

For one brief moment in time, Mike Vail was heralded as the future of the Mets. Instead, all he did was convince a general manager to make an ill-fated decision, one that brought the Mets back to its ugly past. It would take years for the team's future to be bright again.

Note: One Mo-MET In Time is a thirteen-part weekly series spotlighting those Mets players who will forever be known for a single moment, game or event, regardless of whatever else they accomplished during their tenure with the Mets. For previous installments, please click on the players' names below:

January 5, 2015: Mookie Wilson

January 12, 2015: Dave Mlicki

January 19, 2015: Steve Henderson

January 26, 2015: Ron Swoboda

February 2, 2015: Anthony Young

February 9, 2015: Tim Harkness

February 16, 2015: Kenny Rogers, Aaron Heilman, Tom Glavine